The Seattle Times just published this piece by Jenny on the emergence of the “third tier” of publishing, and what we can learn from the blogging revolution.

WHEN I was a young New York Times technology reporter at the turn of the millennium, we scrupulously defined “blog” as short for “web log,” followed by helpful descriptions now wince-inducing in their narrowness — “a personal website” or an “online diary.”Within six years, blogs and online-first media have become an ascendant force in the political — and cultural — landscape.

The book-publishing industry is now going through the same painful transition, as the world’s largest book fair, Frankfurt Book Fair, opens Wednesday in Germany. It’s a perplexing time for authors. Opportunities are shrinking with the publishing houses who have long underwritten the livelihoods of writers. Meanwhile, Amazon.com and other e-reader and tablet platforms beckon with promises of potentially lucrative self-publishing that bypasses traditional gatekeeping and distribution.

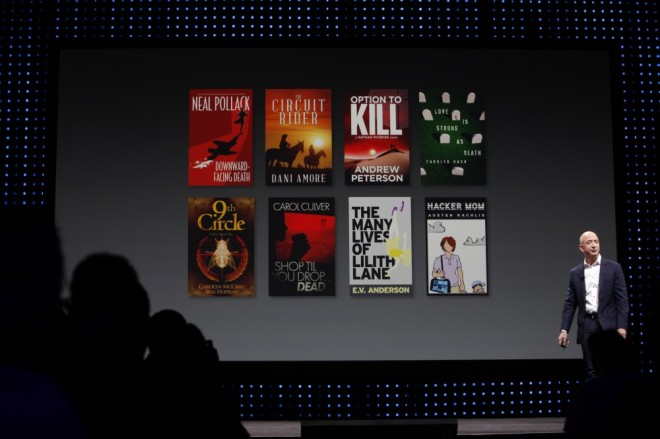

Of the 100 best-selling titles of all time on the Kindle, an astounding 27 were directly released through Amazon.com’s self-publishing platform. But do-it-yourself publishing is burdened by DIY marketing, copy editing and cover design. It’s a distressing path for writers who just want to write.

But a new choice will emerge, if changes in journalism over the past decade serve as a guide.

In journalism, a watershed moment came in 2004, when the Democratic National Convention credentialed 36 bloggers as members of the media. (My article headline: “Year of the Blog? Web Diarists Are Now Official Members of the Convention Press Corps”). And by the 2008 presidential election, blogs and online-first media had come to dominate politics. One-person endeavors, such as Talking Points Memo and Daily Kos, matured into full-fledged businesses.

Investor-backed ventures such as The Huffington Post and Politico were launched (now both have won Pulitzer Prizes). And by then, The New York Times and other media stalwarts had taken the cue, rolling out their own expanding suites of blogs.

So we see a sequence: Legacy media organizations — in this case newspapers, magazines and cable networks — are buffered by a Cambrian explosion of individual voices initially viewed with a “not-one-of-us” disdain by the establishment. In between, a third tier is rising that combines the scale and rigor of enterprise with the nimbleness of the newcomers.

That third tier is now emerging in book publishing, bringing together the production quality and professional aesthetic of the imprints with the flexibility and speed of a digital-first mindset.

Startups, such as the Atavist and Byliner, started with short-form nonfiction, and are expanding. Hollywood producer Scott Rudin and media mogul Barry Diller recently announced a headline-grabbing $20 million investment in their new digital-publishing venture, Brightline. New companies are targeting romance and erotic literature, one of the most vibrant areas in e-publishing.

My first book was published by a traditional publisher. My new literary studio, Plympton, is making a bet on serialized fiction for digital readers.

These digital opportunities will be good for writers, and readers, in the long run. More efficient distribution and “printing” frees us from the cost constraints of paper, brick and mortar. Publishing can open itself up to creative new formats and the resurgence of old ones. Just as television allowed for a viewer experience distinct from that in movie theaters, digital readers can give us a different experience from the dead tree. Already, we are seeing experimentation with serials, novellas, subscriptions and lending libraries. Books can be re-imagined. Novels can be updated.

To be sure, there are worrisome trends that come from a shifting landscape: concentrated market power, fragmented platforms, incompatible and rival formats, demands for exclusivity and a drumbeat of legal battles.

Marketing of e-books (unless you are Amazon.com) is still an amazingly hard nut to crack. There is no effective equivalent for the front table at a bookstore and accelerating readers’ discovery of new titles along an infinite digital bookshelf is neither art nor science yet.

The publisher who solves that challenge will discover a large part of the formula for long-term success.

Jennifer 8. Lee is co-founder of Plympton, a literary studio focused on serialized fiction. She is the author of “The Fortune Cookie Chronicles” and a former New York Times reporter who splits her time between Boston, San Francisco and New York.